Conversation

🥳 Feedback Received!

Thanks for taking a moment to share your thoughts — it genuinely helps us make each chapter sharper.

What happens next:

- Your feedback goes straight to our product team.

- We’ll use it to refine lessons, clarify examples, and make the program even more useful.

Appreciate you helping make this program better for everyone.

Ready for your next challenge? 👇

Growth strategy (the missing link)

What Strategy Means Here

As we saw back in Part 1, strategy is not a list of tactics. It’s not your KPIs, it’s not a roadmap, and it’s not a mission statement.

Good strategy means:

- Identifying the right problem.

- Diagnosing its root causes.

- Setting the boundaries you must operate within.

- Defining the plan of attack that informs how and what you’ll do to solve the problem.

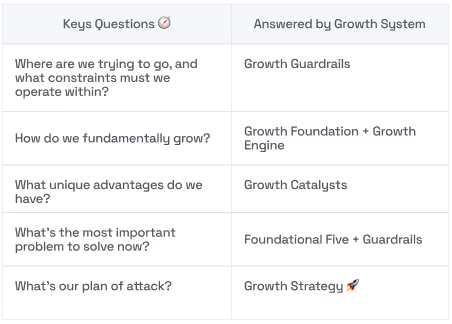

Within this program, your strategy is framed around five key questions:

- Where are we trying to go, and what constraints must we operate within?

- How do we fundamentally grow?

- What unique advantages do we have?

- What’s the most important problem to solve now?

- What’s our plan of attack?

What You’ve Answered So Far

At this point in the program, you’ve already built the inputs that answer the first three questions:

- Guardrails → tell us where we’re trying to go, and the constraints we must operate within (Q1).

- Foundational Five and Growth Motions → show us how your company fundamentally grows (Q2).

- Growth Advantages (Catalysts) → surface the unique advantages that can amplify growth and provide leverage (Q3).

And to sweeten the deal, you’ve even developed your Story System, which provides the fuel you’ll carry into the execution layer.

What’s Still Missing?

That leaves two questions unanswered:

Q4: What’s the most important problem to solve now?

In the context of this program, we’re defining that problem as the lack of a growth engine: a predictable, controllable, scalable way to acquire customers. That’s why you’re here.

Q5: What’s our plan of attack?

That’s the focus of this lesson and this part of the program.

Defining Your Plan of Attack

This stage is about defining your plan of attack. You’ve already identified the most important growth problem: the absence of a repeatable, scalable engine for acquiring customers.

Now the question becomes: how will you solve it? The goal here isn’t to name every channel or tactic. It’s to translate your guardrails, motions, and advantages into a plan of attack.

Side note: For any fellow strategy nerds, you may notice “plan of attack” has a similar meaning to Richard Rumelt’s (author of Good Strategy, Bad Strategy) “guiding policy.” Our strategy framework is a simplified version of Rumelt’s, designed specifically for startups.

A clear approach that tells you which kinds of plays are on the table, which trade-offs you’re willing to accept, and where you’ll concentrate your effort. That plan of attack becomes the bridge between diagnosis and execution.

Think of it this way:

- Your guardrails define the destination and limits.

- Your foundations and motions define the architecture of how growth is possible.

- Your advantages and story provide the leverage and fuel.

The plan of attack is how you tie these together into a clear policy for how you’ll approach acquisition, monetization, and retention.

Why Not Skip This Step?

You may be tempted to jump straight into channels and tactics. But without a guiding policy, you run the risk of:

- Chase shiny objects that don’t fit your foundation.

- Pick channels that can’t possibly work within your economics.

- Misalign your efforts with your advantages and constraints.

This step ensures that when you select channels, pricing models, or retention tactics, they work with your system instead of against it.

Now, all this might sound great in theory — “diagnosis, context, guiding policy, plan of attack.” But we know from years of working with founders and startup teams that strategy can still feel abstract.

To help this really click, we’ve found it’s often easier to step outside the startup world entirely.

So, let’s take a look at strategy being applied in another context that isn’t traditionally top of mind when you think “strategy.”

Doctors Are Strategists, Too

Imagine you’ve been feeling headaches and dizziness. You go to the doctor, and your blood pressure test comes back high.

A lazy doctor might stop there: Diagnosis: hypertension. Action: prescribe drugs.

But a good doctor doesn’t, because the test result alone isn’t the whole story. They know effective treatment requires understanding the broader context:

- The patient’s age, lifestyle, and medical history.

- Other conditions that could make certain drugs dangerous.

- The patient’s own goals. Maybe they want to avoid lifelong medication if possible.

- Potential tradeoffs: one drug might lower blood pressure effectively, but cause fatigue or other side effects that leave the patient worse off.

The doctor then builds a treatment plan. For this patient, given their diagnosis and context, the general approach is as follows: focus on lifestyle changes first, escalate to medication if needed, and avoid certain medications due to potential side effects.

Finally, they translate that plan into specific actions: cut salt, exercise daily, or prescribe a particular drug/dose.

Just like medicine, good strategy in startups isn’t about jumping straight from a symptom (ARR flat, CAC too high, churn spiking) to a prescription (“buy more ads”).

It’s about disciplined diagnosis, considering context, and defining a guiding policy before committing to specific actions.

Now, let’s map this back to growth strategy.

- Signal / Symptom: In medicine, high blood pressure. For your startup, it’s the lack of predictable, scalable customer acquisition (or signals like flat revenue, high CAC, etc.).

- Diagnosis: Doctors identify why blood pressure is high. For you, the root cause is clear: you don’t yet have a growth engine.

- Treatment Plan (plan of attack): Just as a doctor determines a plan of attack based on diagnosis and patient context, startups must synthesize their own context into a guiding policy:

- Goals → what outcomes you’re aiming for (just like a patient’s goal may be to avoid lifelong medication).

- Constraints → the limits you must operate within, from cash runway to team capacity (like a patient’s medical history or allergies).

- Advantages → your growth catalysts, the edges working in your favor (like a patient’s youth or otherwise healthy profile).

- When you pull these threads together, you get your rules of the game for building a growth engine.

- Actions: Doctors prescribe specific lifestyle changes or drugs. Founders choose specific channels, pricing levers, and retention tactics.

Let’s take a look at one more example before you move on and develop your own plan of attack.

Startup Example: Consumer Collaboration App

Imagine a consumer collaboration app designed to help groups organize projects together.

Guardrails:

- Goal: Grow from 50k users → 500k users in 18 months.

- Constraints: Team of 6, $1M in venture funding, but runway capped at 18 months.

- Growth Economics: Target CAC of $20. Need CAC payback within 6 months.

Growth Catalyst:

- A network effect flywheel — the app becomes more valuable as more users within a group adopt it.

Foundational Five (current state):

- Market: Large TAM (tens of millions), but highly competitive.

- Product: Strong collaboration features, but onboarding is clunky and unintuitive.

- Model: Subscription-based, with a freemium tier.

- Brand: Currently undifferentiated but overhauling with Story System.

- Channel: Users have been acquired almost exclusively through word of mouth. Half of their users came via a few viral influencer posts that happened completely by chance.

Motions

- Acquisition: Content-led + virality booster. Content attracts interest and reinforces credibility, while virality helps accelerate adoption via sharing.

- Monetization: Product-led. Free trial → subscription fits the ARPU and usage profile.

- Retention: Product-led. Success depends on habit loops and users embedding the app into daily routines.

Diagnosis:

- Signal: Growth has plateaued. New user sign-ups have stagnated.

- Context: Most acquisition is still coming from chance word-of-mouth and viral influencer posts that we can’t replicate. Aggressive growth targets (10× in 18 months) but only 18 months of runway. Product has strong collaboration features but clunky onboarding; brand is still undifferentiated. Our growth advantage is a network effect flywheel, but it only activates with enough users.

- Problem: The absence of a scalable, controllable acquisition engine. Without fixing onboarding and building repeatable acquisition channels, the flywheel can’t start spinning.

Guiding Policy / Plan of Attack:

- Prioritize low-CAC, high-scale channels (content-led motions with paid assists) that allow us to acquire users as quickly as possible in order to reach critical mass and get our network effect flywheel spinning.

- Reduce onboarding friction so it doesn’t cause our flywheel to stall.

- It must be as easy and intuitive as possible for our users to invite others into the product.

Project: Define Your Plan of Attack

Now it’s your turn to bring everything together.

So far, you’ve built the inputs: your Guardrails, your Foundational Five, your Growth Advantages, and your high-level Motions. The next step is to synthesize them into a clear Plan of Attack for how you’ll approach building a scalable growth engine.

Here’s how to structure your entry in the Plan of Attack section of your Master Strategy Project:

Diagnosis

- Signal: What indicators are you seeing? (e.g. flat revenue, stalled acquisition, low retention).

- Context: Constraints, goals, foundation, and advantages that shape what the signal means.

- Problem: The most important growth problem to solve now. (By default in this program, that problem is the lack of a scalable growth engine.)

Plan of Attack (Guiding Policy)

- The motions you’ll lean on (acquisition, monetization, retention) and why they fit your foundation.

- How your guardrails and foundation shape what’s viable.

- How your advantages give you leverage.

- The rules of the game you’ll follow as you move into execution.

Keep it to 2–3 tight paragraphs. The goal is not a play-by-play of tactics yet. It’s to capture the synthesis: your growth diagnosis and your plan of attack for solving it.

You’ll refine this as you move into the next modules: Acquisition Channel Strategy, Monetization & Pricing Strategy, and Retention Strategy.