Project: Calculate your ARPU and target CAC (Acquisition Strategy Part 1.4)

Customer acquisition cost and annual revenue per user are essential metrics for all startups. You need to know how much a customer is “worth” (ARPU), how much you can afford to invest in acquiring a new one (target CAC), and how those numbers do—and should—relate to each other (ARPU:CAC ratio).

We’ll refer to CAC and ARPU pretty extensively in our discussion of business model fits that starts on the next page. It’ll be helpful to know what yours are before we dive in.

Annual revenue per user

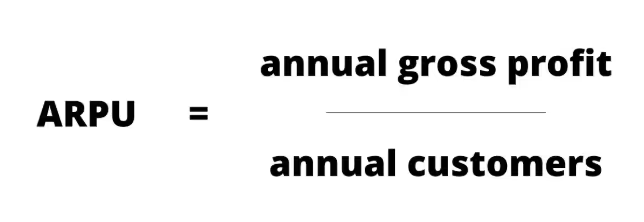

ARPU uses a basic formula. Divide your annual gross profit by the number of customers you have:

Your annual gross profit is your revenue minus cost of goods sold (COGS). To calculate COGS, add up all the expenses that go into creating your product, as well as the expenses required to support existing customers (such as tools and salaries for customer success and/or support teams).

Companies that target enterprise, like Salesforce and Palantir, tend to have high ARPUs. Social media companies like Pinterest and Reddit have low ARPUs.

Project: Calculate your ARPU

Using the above formula, calculate your ARPU. Add it to your project doc.

If your startup is very early-stage or hasn’t been around a full year, project your ARPU using a combination of common sense and any data you have.

Determine your target ARPU:CAC ratio

How much should you earn per customer compared to how much you spend to acquire one? This is your ARPU:CAC ratio. It’s crucial to know as you launch an acquisition strategy. Without it, you run the risk of either burning through your capital or growing more slowly than you could.

An important element to consider when determining your ARPU:CAC ratio is your payback period.

Payback period

ARPU and CAC don’t tell the full story. If two companies have the same ARPU:CAC ratio, but one recoups its CAC in six months and another takes 20, the first will grow much faster.

Your payback period is the amount of time it takes to recover your CAC, before you break even.

A startup with a short payback period can reinvest in growth more quickly. They’re less likely to have cash flow issues. On the other hand, if it takes years to earn back the costs you put into acquiring a customer, you might end up using all your resources during that time.

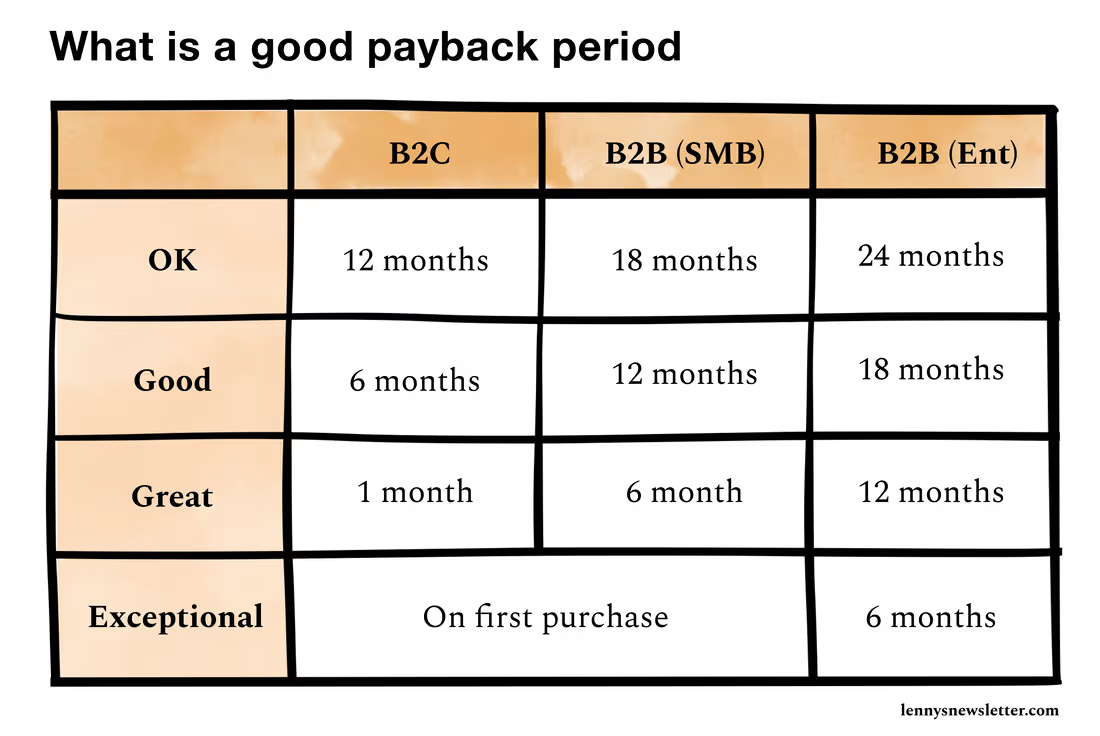

Growth expert Lenny Rachitsky polled fellow marketers to find out what they think a “good” payback period is. Here’s a helpful chart with his findings, which you can use for benchmarking

In general, the longer the payback period, the higher the ARPU:CAC ratio needs to be.

Here’s what we recommend for target ARPU:CAC ratios

For companies that earn the bulk of their revenue upfront, or for companies with a monthly recurring revenue (MRR) that’s constant during the lifetime of a customer, we recommend an ARPU:CAC ratio between 2:1 and 3:1. That means you’re earning about $2-3 for every dollar spent to get a customer.

For companies that expect the bulk of their revenue to come during later stages of a customer’s life cycle, our recommendation is an ARPU:CAC ratio between 3:1 and 4:1. An example would be a SaaS product that starts customers out on a low-priced entry-level plan, which they eventually upgrade from after using the product for months or possibly years.

Those ratios are on the conservative side. Consider them a floor/minimum that it can be risky to go under. That said, a lower ARPU:CAC ratio might be appropriate if you’ve raised a lot of money and need to grow as quickly as possible. Alternatively, going higher could make sense for a startup with limited capital that needs to run lean, or one that takes less risk.

But in general, the above ratios strike a balance between being aggressive and not burning through capital too fast, between spending too much and too little to grow your customer base.

As with any benchmark, take this one as a general guideline—one that should be adjusted over time based on your company’s goals. As your startup matures, you might decide to prioritize profitability more. You would increase your ARPU:CAC ratio. Or if you want to stay in pure growth mode, you might leave it as is or lower it.

Bonus: Why we use ARPU:CAC instead of LTV:CAC

If you’ve been in the startup world for a while, you might be surprised to see that we use ARPU:CAC instead of the more common LTV:CAC. If you’re curious why, read this section; otherwise, you can skip ahead to estimating your target CAC.

Lifetime value (LTV) is how much you expect customers to pay you during their relationship with your company. It’s similar to ARPU, but whereas ARPU looks at the average revenue that a customer will produce in a single year, LTV looks at the revenue produced over an entire relationship between a customer and a company.

The problem with using an LTV:CAC ratio for business decisions is that early-stage startups won’t know what their LTV actually is. It often takes years to measure it. That’s especially true for companies with multi-year customer relationships, and for those that earn the bulk of their revenue in the later years of the customer life cycle.

Trying to use LTV to decide how much to spend on acquiring customers is risky. It’s a guessing game—and given the stakes, we encourage startups to avoid guessing as much as possible.

If your company has been around for a few years, and you do have a good sense of your LTV, feel free to use it instead of ARPU in relation to CAC. If that’s the case, add one to the recommendations we gave earlier:

- For companies with short payback periods, use an LTV:CAC ratio between 3:1 and 4:1.

- For companies with long payback periods, use an LTV:CAC ratio between 4:1 and 5:1.

Find your target CAC

Now that you know your ARPU and what you want its relationship with your CAC to be, finding your target CAC is easy. Just plug it into your ratio.

If your ARPU is $90 and you think a 3:1 ratio is best for your startup, your target CAC would be $30 ($90:$30 = 3:1 ARPU:CAC ratio).

That’s the maximum amount you should spend to acquire a new customer. It’ll be your most important metric later, when you decide which acquisition channel to center your growth strategy on.

A few things to note about CAC:

- When considering how much you’ll be spending on new customers, factor in all expenses tied to customer acquisition. That includes ad costs, salaries, management systems, overhead, etc. But exclude expenses tied to customer retention—CAC is only for new customers, not returning ones.

- Use CAC for new paying customers, not prospects who have signed up for free trials or freemium.

Project: Calculate your unit economics

Here are the main takeaways from this page:

- Calculate ARPU by dividing annual gross profit by annual customers.

- Understand your payback period—how long it takes to break even on your costs to acquire a new customer.

- Determine your ARPU:CAC ratio, using a 2:1-3:1 or 3:1-4:1 baseline.

- Use your ARPU:CAC ratio to establish your target CAC.

Add your unit economics as well as your pricing strategy to Part 1.4 of your Acquisition Strategy doc.

Note: The last three lessons in this module will help you further hone your pricing strategy. If you decide to modify your approach after going through them, be sure to update your Acquisition Strategy doc to reflect your finalized strategy.