Conversation

How can I assist you today?

No results found

Try adjusting your search terms or check for typos.

The Tactics Vault

Each week we spend hours researching the best startup growth tactics.

We share the insights in our newsletter with 90,000 founders and marketers. Here's all of them.

Creative as a Supply Chain

Research from the Demand Curve team.

The Signal

What changed.

Meta’s GEM now orchestrates multi-ad sequences across a user’s entire experience. Bidding and targeting are increasingly automated, making creative one of the highest-leverage inputs left.

The Hypothesis

The emerging thesis we’re exploring.

A growing number of operators believe the top-performing advertisers over the next 12-18 months will be the ones that treat creative as a supply chain — an operational function with production cadences, QA gates, and feedback loops, not just a strategic or artistic one.

The Big Picture

The structural shifts behind the hypothesis.

Andrew Faris (former CTC head of strategy) nails it: Meta ads scaling has two stages. Stage 1 is finding creative that resonates (a strategic problem). Stage 2 is scaling it into diverse assets (an operational problem). Most brands fail to make the transition.

Why does this matter now? GEM optimizes across your entire creative library simultaneously. It needs volume, but only genuine diversity counts. When volume becomes the constraint, we're now looking at a supply chain problem.

- Creative is one of the last high-leverage inputs. Meta is removing manual controls. GEM optimizes across your entire creative library, but data strategy and conversion events still matter. One brand produced 299 net-new concepts in a single month.

- Lazy variants get punished. Same image, different text overlay = same creative, higher CPMs.

- Organic signals now feed ad delivery. Content that performs organically gets algorithmic priority in paid.

- The media buyer role is evolving into a creative strategist. The growth edge is understanding why certain creative resonates with certain audiences.

- Most organizations aren’t ready. Fewer than 30% have internal expertise to evaluate AI in creative production.

What’s Working

Where the thesis meets execution.

- Kynship’s creative flywheel — Develop/deploy/maintain framework. 150+ creatives per campaign launch. Stage 2 as an operating system.

- Foxwell’s GEM-era testing framework — How to structure tests when GEM optimizes across sequences, not individual ads.

- Perpetual Traffic GEM deep dive — 30+ fresh concepts/month minimum. 5-7 creators based on spend. Two hours of detail.

- Jess Bachman’s anti-“spray and pray” — Best ads possible, real spend, analyze WHY, iterate.

- Barry Hott’s ugly ads — 3x click rate, 3-5x conversions vs polished creative. $600M+ in spend. Intentionally lo-fi.

- HexClad’s organic-to-paid flywheel — Slack channel where organic wins get flagged for paid testing. Any team can do this Monday.

- The “Feeder Strategy” — CTR from 6.2% to 11.95%, CPC down 48%. Specific enough to implement this week.

Frontier Players

The operators at the center of this shift.

- Andrew Faris — Former CTC head of strategy. Two-stage framework for creative scaling.

- Jess Bachman — 7-figure agency in one year. Check out the agent he built on Motion.

- David Herrmann — “Have as many diverse ads as Meta will spend on.”

- Connor Rolain — Cleanest organic-to-paid loop in DTC.

- Savannah Sanchez — 200+ ads/week. 50+ clients. iPhone shoots, 5-day cycles.

- Kynship — Most operationalized creative flywheel in DTC.

- Cousin Labs — Creative velocity is the backbone of their methodology.

- Creative Milkshake — 2,000+ ads/month. 200+ brands. 6 languages.

- Motion — Expert Agents codifying top creative strategists into AI.

- Jarvis Su — Building the AI Creative Director playbook from scratch.

- Sarah Levinger — Behavioral science applied to creative strategy.

- Ashley Rutstein — Traditional ad craft meets performance marketing. Plus we just like her vibe.

The Stack

Tools for building the creative supply chain.

Creative Intelligence

- Motion Expert Agents — Dara Denney, Barry Hott, Jess Bachman methodologies as AI. Analyze your creative, get recs.

- Segwise — Tags every creative element, maps to performance. Cross-platform. Only tool analyzing playable ads.

- VidMob — 3 trillion creative tags. OCR, voice analysis, frame-by-frame cataloging.

- Neurons — Predicts ad response before launch. 20 years of eye-tracking data. 95%+ accuracy.

Creative Production

- Celtra — Modular creative automation. 18,000 creatives for one campaign in 3-5 days.

- Foreplay — 100K+ new ads daily. AI brief builder. Expert collections from top strategists.

- MakeUGC — AI-generated UGC videos. 100+ avatars, 29 languages. Full content ownership.

- ChatCut — Edit video by editing the transcript. AI-powered, 60-80% faster than traditional editing.

- Seedance 2.0 — ByteDance’s cinematic AI video generator. Native audio, physics simulation, character swapping. Rolling out on CapCut.

- Sora — OpenAI’s text-to-video. Beware: it's addicting.

- Kling — Video generation. Strong motion and physics. Popular with ad creators for product demos.

- Veo 3 — Google DeepMind’s text-to-video. High-quality generation from prompts.

- Pomelli — Google Labs. Analyzes your site, generates on-brand ad creative and copy.

- Nano Banana 2 — Google’s AI image generator. New version just dropped today.

Signal vs Noise

The counter-arguments, and whether they hold up.

💨 “Creative velocity is everything. Just ship more ads.”

🎯 Maybe. But the most interesting counter-evidence comes from inside the volume camp itself. Jess Bachman built a 7-figure agency doing the opposite: fewer ads, real spend, deep analysis of WHY each one worked. The 299-concepts brand is a compelling data point, but so is Bachman’s results. It’s possible the winners aren’t winning because of volume. They’re winning because volume forces diversity, and diversity is the actual variable.

💨 “More volume = more creative”

🎯 GEM treats lazy variants as the same creative and charges you more. Fifty versions of the same hook is one ad, not fifty. Volume without genuine diversity is just expensive noise.

💨 “AI will replace creative teams”

🎯 AI ads only win when they don’t look like AI. 500M impressions, 3M clicks: human-directed AI outperformed both pure-human and obviously-AI. AI belongs in the middle of the pipeline, not at the top.

💨 “Polished creative wins”

🎯 So do ugly ones.

💨 “You can’t systematize creativity”

🎯 Stage 1 is strategy. Stage 2 is logistics. The best teams separate them. You don’t systematize the inspiration. You systematize everything around it.

One more thing worth noting: Right now, this trend is most visible in DTC and consumer. B2B operates in a fundamentally different environment: smaller addressable audiences, longer sales cycles, fewer products. Whether the creative supply chain model translates to B2B is an open question.

Rabbit Hole

If you wanna go even deeper.

- Creative Strategist Rising — The definitive guide to the role at the center of all this.

- GEM Technical Paper — The source document. For readers who want to understand the algorithm itself.

- Taboola/Columbia/Harvard: AI Ads That Work — Most rigorous AI vs human creative study. 500M impressions.

- Creative Strategy Summit 2025 — Dara Denney, Savannah Sanchez, Sarah Levinger. Best single event on where this is heading.

The great market(ing) overcorrection

Insight from Justin Setzer — Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

A few years ago, a good friend of mine decided to take the leap and start his own growth agency. Very sharp guy. Top-notch growth operator. And for a while, things were good. But we caught up last week, and he informed me that he was going to have to close up shop. We spent a while on the phone unpacking what happened, trying to make sense of the landscape right now.

I told him that while it may not mean much, he's not alone. I've talked to a dozen agency operators this year alone. Four are shutting down. Seven don't know if they'll make it through 2026. Only one said things are business as usual.

Of course, some of it’s just the nature of the beast. Growth and marketing agencies have some brutal structural dynamics. Things like the reverse retention paradox, where the better you perform for a client, the harder it can be to retain them (not too dissimilar to dynamics at play with dating apps). Or the growth expert paradox, where the skills that make you great at growing other companies are underutilized in terms of growing your own business. Both worth exploring another time.

But the thing that kept coming up, the thread running through almost every conversation I’ve had recently, isn’t specific to agencies. It’s hitting everyone.

Losing sight of what actually matters

Here’s a story that captures it perfectly. Another friend of mine does a lot of advisory/fractional work. He's been working with a client to bring on an SEO specialist. Had a great partner picked out, contract nearly signed.

Then the client sent him a LinkedIn post. Something about an AI-powered workflow that "could replace your whole SEO team." (It was a handful of basic AI prompts 🤦♀️.)

The client wanted to blow up the entire deal. “Why would we pay $9,000 a month for an agency if this guy's AI can do it virtually for free?”

My friend had to talk him off the ledge.

This is happening everywhere right now. And it points to something I think we need to be honest about: There's a massive difference between producing something and producing something better. And right now, almost nobody is asking which one they're actually getting.

Most people's thinking stops way too early. Can AI do the task? Yes. Does the output look decent? Kinda. Great, fire the team.

But since when is "decent output" how we evaluate anything? You already had good. You had experts. You had people who knew what they were doing. The question was never whether AI can spit something out. The question is whether it produces better results than the people you just laid off. And if you can't prove that, you didn't make a strategic decision. You made a vibes-based one at the expense of someone else's career.

Look, I could probably remove your appendix if you asked me to. Give me a couple YouTube videos and, well, something's coming out.

But that was never really the goal, was it? The goal wasn't "remove the appendix." The goal was to remove it safely, with minimal damage, fewest complications, and the highest chance of a good recovery. You know, the stuff a surgeon spends a decade learning how to do.

But that's what's happening in marketing right now. Companies are acting like the only goal is to get the appendix out.

Dial down the hype

Let me give you another example. I read a newsletter last week about a company claiming they have 40 employees, 20 human and 20 AI. The piece was sprinkled with lines like “the line between human and AI has never been more blurry.”

I'm sorry, but what the actual fuck are we talking about?

There's nothing blurry about it. You have 20 employees. You wrote 20 scripts, gave them names, and for some reason are calling them employees.

And this stuff has consequences. Because the pattern I keep seeing goes like this: someone on LinkedIn announces they’ve “automated their entire sales process” or “replaced their content team with AI.” Amazing. That’s the input. What’s the output? What happened to revenue? Pipeline quality? Brand perception?

I'm still waiting for someone to cover that part.

At this point, I imagine someone's reading this thinking I must be anti-AI.

I'm not. I use the shit out of AI. As a non-technical founder, I've never felt more empowered. It's genuinely incredible.

But I've spent my entire career helping operators cut through noise and focus on what actually moves the needle. That's the whole point of what we do at Demand Curve. Ignore the shiny objects. Think from first principles. Be ruthlessly evidence-based about what's working and what isn't.

And when I apply that same lens to what's happening right now, I'm not seeing the evidence. I'm seeing a lot of activity, a lot of hype, a lot of breathless claims. But I'm not seeing proof that the trade-offs being made are worth it.

The self-fulfilling prophecy

Here’s where it gets extra tricky.

A marketing executive reads one of these LinkedIn posts, or hears it secondhand from another executive who’s equally caught up in the hype. FOMO kicks in. They convince themselves a smaller team plus AI can do more. So they lay people off.

Those talented people, now unemployed, turn to freelancing. A lot of them. All at once.

Basic economics: when supply floods a market and demand stays flat (or in this case, decreases), prices drop.

So what happens next? These same executives who cut their teams can now hire talented freelancers for a fraction of what they used to cost.

And they celebrate. “See? I told you we could get more for less. AI is bringing down the cost of marketing.”

No. You made an emotional decision like a child. You flooded the talent market. Your fear-driven behavior helped suppress demand. And then you congratulated yourself for your role in creating a toxic positive feedback loop.

Where the market is actually shifting

So that's the cycle at play. Or my theory of the cycle, at least. Here's how it's reshaping the market:

SMBs and early-stage startups are stepping down-market (even more). They were already working with relatively affordable talent and scrappy solutions. Now they’re looking at AI and thinking, “Our output isn't great as it is. And every dollar counts. If there's a way to reduce costs without taking a big hit on quality, we may as well.” Fair enough. That’s rational for their situation.

Mid-market companies are the most interesting segment to me. And it seems they're also taking a step or two down market. And it's hard to blame them. All those marketers getting laid off from bigger companies? Falling right into the laps of these companies. That $30k/mo. agency that your investors pressured you to bring on isn't looking so appealing with so much talent on the market.

Large companies are mostly in holding patterns, waiting to see what happens from the cuts they have already made. They’re keeping their strategic talent and advisory relationships. The layoffs hit execution layers hardest.

Basically, that leaves a gap in the middle. Or at least what used to be the middle. And if you’re a marketer or agency operator, understanding where that gap is opening up matters a lot for what you do next.

What's the solution?

Alright. This has been a bit of a rant. We had a blizzard here in NYC, I haven't left my apartment in a while, so maybe I'm feeling a little extra spicy.

But ranting wasn't the whole point. My aim is to help shine some light on the market dynamics I believe are at play, so people can figure out how to respond.

If you're a marketer: The answer isn't just "get better at AI." You have to, obviously. But that's table stakes. The real move is the same thing the best marketers have always done — help decision-makers make better decisions. If your leadership team is making reactive, half-baked "strategic" decisions based on vibes, your job is to be the person in the room with actual data. Build the systems to quantify what AI is actually doing for your function. Not "we produced more content." What happened to pipeline? To revenue? To the metrics that matter? Don't accept bad decision-making. Challenge it. Respectfully, sure. But challenge it.

If you run an agency: What you're feeling right now is not a personal failure. The environment is genuinely brutal. But if there's a hole forming in the middle of the market, you've got two paths. Move upstream — get valued for how you think, how you solve problems, your strategic judgment. Or move downstream — figure out how to deliver real value at scale for a lower price point using the very tools that are disrupting you. Sitting in the middle and hoping things go back to normal is probably the worst option.

If you're a startup founder: Be honest with yourself about whether your AI investments are producing real improvements or just short-term cost savings. There's a difference. Cutting your marketing team might improve your bottom line this quarter. But are you maintaining the quality? Are you still investing in the few levers that have long-term, defensible value? Or are you being short-sighted and calling it efficiency?

Finally, to all the big co executives (and I may as well throw VCs into the mix too): I spent some time trying to figure out how to put this in a more eloquent way, but it's getting late, and I'm not one for mincing words anyway. So here goes: Get your head out of your ass. Learn what your teams actually do. Understand how the work actually gets done before you decide a prompt can replace it. Maybe even come on down from that ivory tower you love so much and stop making decisions based on what another executive told you at a dinner party. You are making choices that impact real people's livelihoods and careers. If you can show me data that your AI-augmented, leaner team is producing better results — genuinely better, not just cheaper — I'd love to see it. But if you can't, maybe sit with that for a minute before you greenlight the next round of cuts.

Justin Setzer

Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

The great market(ing) overcorrection

Insight from Justin Setzer — Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

How teams are using AI for Meta Ads

Research from the Demand Curve team.

This is one of the most recurring questions we're getting right now. Here's what you need to know.

The big picture

Shifts defining paid media in 2026:

- Creative is the new targeting. Meta’s Andromeda algorithm controls targeting now. Creative diversity and volume are the only real levers. Paid social is becoming 80% creative ops, 20% media buying.

- Competitive moat = proprietary data + feedback loops. Sure, creative is the new targeting. That's been known for a while. The real advantage, though, isn't making more creatives. The winners will be those who have (or find a way to generate) proprietary data and the tightest learning loops.

- The media buyer is becoming an AI strategist. The job is shifting from manual optimization to AI systems architecture. IAB Lab released an agentic AI roadmap. Platforms are building autonomous buying infrastructure. The skill isn't disappearing, but it is shifting from "manage campaigns" to "architect the system."

- Campaign architecture is collapsing. Advertisers who consolidated to 2-campaign structures saw 32% CPA drops.

- Organic content now feeds the paid algorithm. Organic posts, Reels, and videos now directly influence ad ranking. The boundary between paid and organic has dissolved.

- Ads are coming to ChatGPT. OpenAI is testing ads inside ChatGPT as of this month. An entirely new channel is forming.

- The entire ad engine was rebuilt. Andromeda + GEM didn’t update the old system; they replaced it.

Inside look

- Taylor Holiday built Compass — a system that calculates monthly ad volume from financial models, then uses AI to generate creative angles from 30 psychological purchase drivers. The most sophisticated operator-built AI infrastructure we’ve seen described publicly.

- Dara Denney encoded her creative analysis framework into an AI agent. Pick any ad in your account and it diagnoses performance against her proven framework. Systems that scale your judgment, not replace it.

- FULLBEAUTY Brands used Meta’s native Advantage+ Creative AI to replace plain white catalog backgrounds — 45% higher ROAS, 22% higher conversion rate, 36% higher CTR. One of the clearest wins for Meta’s built-in AI tools.

- Jon Loomer built JonBot — an AI trained on 700+ pages of his content. He shares where it speeds him up, where it fails, and the guardrails he’s built. Honest and practical.

- Motion surveyed 500+ advertisers: 86% plan to increase AI use for creative ideation, but 55% aren’t convinced by output quality. Nielsen found consumers find AI-generated ads “annoying, boring, and confusing.”

Frontier players

Operators doing interesting work at the intersection of AI + Meta Ads.

- Cody Plofker — CEO of Jones Road Beauty. Writes weekly with real numbers from a brand he actually runs.

- Dara Denney — $100M+ in Meta spend. Building AI agents for creative analysis.

- Taylor Holiday — CEO of CTC. Analytically rigorous. Will challenge your ROAS assumptions.

- Andrew Foxwell — Runs Foxwell Founders (500+ advertisers, $300M+/mo in Meta spend).

- Jon Loomer — Old school, yet still cutting-edge.

- Shanik Patel — Ex-Grammarly. Fascinating work with AI + video ads.

- Barry Hott — $600M+ managed spend. His “ugly ads” thesis is what Andromeda actually rewards: authenticity > polish.

- Sarah Levinger — Living at the psychology × creative × AI intersection. Works with Hexclad, True Classic, Fabletics.

- Rob Leathern — Former VP Product at Facebook. He literally built the systems that govern how Meta ads work.

The stack

AI tools for Meta ads.

Creative Generation

- Arcads — AI UGC video ads. $16M seed (Sequoia Scout). 100K videos/month. Hit profitability with 7 employees.

- Creatify — End-to-end AI video ads from a product URL. New “AdMax” combines creation + testing + analytics. $15.5M Series A, $9M ARR in 18 months.

- MakeUGC — Scripts to AI UGC with 300+ avatars and product-in-hand demos. Most affordable entry ($49/mo).

- Mintly — AI ad creative studio. Templates reverse-engineered from winning ads. Upload product photo → remade in top-performing formats.

- Pencil — AI ad creation with predicted performance scores trained on $1B+ in spend.

- Runway — AI video generation at cinematic quality for brand-level creative.

Campaign Optimization

- AdAmigo — Autonomous AI media buyer for Meta. Monitors 24/7, catches anomalies, executes via text/voice. $99/mo. Closest thing to replacing a junior media buyer.

- Koast — Bulk Meta ads launching (30 at once), automated stop-losses, multi-account sync. Built for agencies, not marketers.

- AdStellar — 7 specialized AI agents build complete Meta campaigns in 60 seconds. Multi-agent architecture.

- Madgicx — AI Meta ads management. Auto budget reallocation + creative fatigue alerts.

Creative Intelligence

- Segwise — Multimodal AI auto-tags every creative element and maps to performance. Only platform doing element-level analysis.

- Superads — Chat with your ad data. Auto-categorizes winning hooks, triggers, copy patterns. Free tier. By Superside.

- AdSkate — Tests ads BEFORE launch via synthetic audience models. Lidl: 24% CTR boost.

- Replai — Computer-vision AI auto-tags video ads at frame level. Sequoia-backed. Processes $5B+ in spend.

- Motion — Creative analytics. Which ads are winning and why.

- Foreplay — Competitor ad tracking + AI creative briefs.

Competitive Intelligence

- Panoramata — Tracks competitors’ full stack: Meta ads, emails, landing pages, SMS, website changes. 4M+ ads searchable. See the full funnel.

Speaking of staying on the frontier... a quick message from our sponsor, Gather.

What AI tactics are actually useful in your marketing and growth efforts?

Join your peers in San Francisco for a candid conversation about what's working, what's not working, and what the future of AI in marketing/growth looks like in 2026.

Food and drinks will be provided. Limited availability so reserve your spot today!

Signal vs Noise

💨 “We can replace our media team with AI.” AI handles execution (bids, placements, audiences). Someone still needs to architect the strategy, direct the creative, and interpret what’s working. The teams massively cutting headcount are about to learn this the hard way.

🎯 The media buyer role is evolving into an AI strategy architect.

💨 Using AI to generate ad copy and calling it a strategy.

🎯 Using AI upstream — customer research, persona development, creative briefing.

💨 More creative volume = better results. Cody Plofker disagrees: Meta classifies visually similar ads as the “same ad” even with different hooks. His team cut from 4-5 variations per ad to 2-3. Variation testing is “a big cost center and largely wasteful.”

🎯 Creative diversity across angles and formats. Not iterations of the same concept.

💨 Platform-reported ROAS. Every platform’s AI is optimized to make itself look good.

🎯 Incremental Attribution and holdout tests. Your number gets smaller but (a little more) honest.

Rabbit hole

Want to go deeper? Start here:

- Alvin Ding on how Meta’s AI might be damaging your brand — AI slapping music on videos, cropping assets, misrepresenting brand voice. The dark side of Advantage+ without oversight. 📕

- Monica Shukla in AdExchanger on what Andromeda actually changes and what it doesn’t — the most grounded strategic take: brands seeing lift “adjusted not by outsourcing judgment to the algorithm but by refining their creative strategy.” 📕

- Andrew Foxwell on Perpetual Traffic: The Secret to Meta’s Andromeda Revealed (Part 1) and Part 2. From someone running a community spending $500M/mo on Meta. 🎧

- Why you can’t rely purely on direct conversions when measuring Meta Ads success 🎧

Whatcha think?

This is the first edition of The Frontier — a new format we’re experimenting with. We’ll be running this for the next few weeks as we dial it in.

Love it? Hate it? Want different topics? Hit reply. We read 'em all.

How to find your growth lever(age)

Insight from Justin Setzer — Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

Over the last two editions, we looked at two of the most common experimentation mistakes.

First, the 'what vs why trap': how teams conflate “what happened” with “why it happened,” producing false learnings that compound in the wrong direction.

Then we examined why most growth experiments flop; and why the answer isn't bigger, bolder, or more.

Both pieces diagnosed the problem. This one’s about what to do instead.

At the highest level, growth work has two layers: Problem Discovery and Solution Discovery. Problem Discovery determines whether you're working on the right thing. What problems exist, why they exist, which levers influence them, and which one will most efficiently get you to your goal. Solution Discovery is everything after: ideating, prioritizing, testing, and learning.

Most teams spend nearly all of their time on Solution Discovery. The features and tests being shipped. Choosing the perfect prioritization framework, testing stack, etc.

That’s the gap this series has been about.

The bad doctor problem

Here’s a scenario I see constantly. A team looks at their funnel data, sees a big drop-off at, say, checkout, and concludes: “Our checkout page is the problem. Let’s optimize it.”

They Google the latest CRO tactics. They redesign the page. They run a dozen A/B tests. Nothing moves.

Why? Because they acted like the bad doctor. They saw a symptom (low checkout conversion) and jumped straight to a prescription (optimize the page). They never stopped to diagnose the actual problem.

Maybe the checkout page is fine. Maybe the drop-off exists because a page upstream didn’t adequately communicate value. Maybe 40% of the traffic came from dogs who hijacked their owners' laptops.

They’ll never know, because they skipped the diagnosis.

If you caught last week's newsletter, you'll recall how I made some of the very same mistakes early in my career at Grammarly.

What finally worked was stopping and doing the diagnostic work. I talked to customer support. I studied what visitors were seeing in search results before they reached our page. I looked at how our product, pricing model, and competitive landscape all fit together.

Every signal pointed to the same thing: visitors needed to know the product was free, and they needed to see it exactly where they were making the decision. Two words on the CTA button. 8x the lift of any other test I’d ever run.

The diagnosis is what made the solution obvious.

What happens when you get problem discovery right

Over at Lenny's Newsletter, Duolingo’s former CPO, Jorge Mazal, shared the story of how they reignited growth — taking daily active users from single-digit growth to a 4.5x increase over four years (as a mature product, at that!). It’s a great case study, and it happens to perfectly illustrate the power of Problem Discovery.

Their first two attempts skipped it entirely. They saw a problem (growth is stalling) and jumped straight to solutions. They borrowed a game mechanic from Gardenscapes that flopped. They copied Uber’s referral program, which excluded the exact users it depended on. Months of effort, minimal impact. Classic Solution Discovery without Problem Discovery.

The turning point: they stopped shipping and started diagnosing. First, they built a detailed growth model, segmenting their user base by engagement level and mapping how users flowed between segments daily. Then they ran a sensitivity analysis: if we improved each lever by the same amount, which one moves our North Star the most?

The answer was clear: current user retention rate (CURR) was 5x more impactful than the second-best lever. That single finding reoriented their entire strategy. They created a dedicated retention team, deprioritized new-user retention efforts, and focused everything on keeping current users coming back.

That's Problem Discovery. Or at least half of it. They nailed the first part: using a growth model to identify the highest-impact lever. Or, per last week's newsletter, to identify the 'what.' But, like so many teams, they stopped short of pursuing the 'why.'

Where even good teams fall short

Now, it's worth noting: from Jorge's account, they went from identifying the lever to jumping back into solutions fairly quickly. There's almost certainly more to the story than what he covered. We know as well as anyone that it's hard to capture all the nuance in a single essay. But what he chose to share is instructive, because it mirrors what I see most teams do.

Even after doing solid Problem Discovery work to find the right lever, they appear to have skipped the second half: diagnosing why that lever was stuck. Their solution process relied heavily on a single source of evidence — what had worked at other companies (Zynga, in particular). Jorge hypothesized, based on his experience at Zynga, that leaderboards would also work at Duolingo.

It happened to work. But relying on a single evidence source is risky. What if leaderboards hadn’t addressed the underlying issue? They might’ve tried a dozen more features borrowed from gaming companies and gotten nowhere — because they never fully investigated what was actually causing their best users to disengage.

Side note: I'm a firm believer that intelligently borrowing from other companies is one of the most impactful growth tactics out there. But it's much harder done than said. Jorge actually speaks to this in his essay: "I realized that I had been so focused on the similarities between Gardenscapes and Duolingo that I had failed to account for the importance of the underlying differences." That's the whole challenge in one sentence. On the surface, two companies can look extremely similar, yet the tactics that worked for one still completely fail for the other. The question is: what are the underlying differences, and how do you systematically identify them? I've built a framework for exactly this that we use with our agency clients, and it's one of the biggest edges we give them. I've never published it, but I'm planning to in a future edition.

The diagnostic process

The growth community does a great job teaching Solution Discovery: form a hypothesis, design a test, analyze results. What it largely skips is the Problem Discovery process that should come before any of that.

Here’s how it works:

1. Define the goal and constraints.

Where are you trying to go, how much can you invest, and by when? “Grow revenue” isn’t a goal — it’s a direction. “Add $400k in MRR within 90 days without increasing costs more than $50k/month” is actionable. Without constraints, you can’t evaluate tradeoffs between problems worth solving.

2. Map the levers.

Build a growth model. Break your North Star into its inputs. Revenue = customers × revenue per customer. Customers = leads × conversion rate. Leads = visits × sign-up rate. Keep breaking it down until you reach levers you can actually influence.

3. Identify high-impact levers.

You need to understand which levers have the greatest influence on your North Star. How you do this depends on your stage and data. A mature product like Duolingo can run a formal sensitivity analysis by applying a uniform increase to each lever and modeling the output. An earlier-stage company might work backwards from the goal: if we need $50k in new monthly revenue, what are the possible levers, and which ones does our model suggest are most efficient?

Either way, the point is the same: let the math narrow the field instead of guessing which lever "feels" most important.

4. Select the problem worth solving.

Knowing which levers have the most mathematical impact doesn't tell you where to focus. Not in isolation.

You also need to consider: can we actually move this thing? How much would it cost? Is there evidence it's genuinely underperforming, or does the math just make it look attractive?

The right problem to solve isn't always the highest-impact lever. It's the one that best balances impact, feasibility, and evidence — all while staying within the constraints.

5. Diagnose before you prescribe.

This is the step everyone skips. You’ve selected the lever. Don’t brainstorm solutions yet. Ask why that lever is stuck.

Talk to users. Talk to customer-facing teams — support, sales, anyone who hears directly from customers. Study historical data: has this metric always been this way, or did something change? Look at how other companies have solved similar problems. Watch session recordings. Examine what’s happening upstream in the funnel.

You’re building a case, not forming an opinion. The more evidence you layer, the closer you get to the root cause. And the closer you get to the root cause, the more obvious the right solution becomes.

6. Now enter Solution Discovery.

This is where the conventional growth playbook kicks in — and where it actually works, because it's grounded in real evidence. Now we can form testable hypotheses, run them through prioritization frameworks, design experiments, and start generating learnings that help us hone our hypotheses and get closer and closer to the truth.

Steps 1–5 are Problem Discovery. Step 6 is Solution Discovery. Most teams start at step 6. Some start at step 3. Almost nobody does steps 4 and 5. And that's where the real leverage lives.

Why this changes everything

Getting Problem Discovery right doesn’t just improve your hit rate on experiments. It changes the magnitude of outcomes.

Two words at Grammarly — 8x lift compared to far more complicated tests that preceded it. From stalled to 4.5x DAU growth at Duolingo. These aren’t normal results. They happened because the teams did the diagnostic work and landed on the right lever(s) before building anything.

When you understand the problem deeply, even small solutions can produce massive results. When you don’t, even massive solutions produce nothing.

Wrapping up the series

I hope you've enjoyed the three-part series on experimentation. It's a big topic. I did my best to make these editions as simple and actionable as possible, but if you have any questions, just shoot us a reply.

If there's one thing to take away from all of this:

The teams that consistently produce outsized results don’t have a better Solution Discovery process. They have a better Problem Discovery process. (Honestly, having one at all puts you far ahead of most organizations.)

When in doubt, slow down. Focus less on testing and more on understanding what problems exist, why they exist, which ones actually matter, and the levers that influence them.

Justin Setzer

Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

How to find your growth lever(age)

Insight from Justin Setzer — Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

Most brands get Reddit backwards

Insight from Colin James Belyea — Co-Founder at Karmic Reddit Agency

Every other social platform rewards you for talking about yourself until people care.

Reddit is the opposite. If you show up promoting your product, Reddit will quietly make sure no one hears you.

Sometimes that throttling is obvious, like a removed post. More often, it is subtle — your content stays up, but your distribution disappears. Engagement stalls. It feels like you are “posting consistently,” but you are not building reach.

It took us a long time (and more than one burned approach) to understand what was happening. The lesson is simple, but unintuitive:

On Reddit, the fastest way to gain influence is to stop trying to promote yourself at all.

From shadow accounts to trust and transparency

When we first started working on Reddit, we avoided branded accounts. We used anonymous profiles that looked like ordinary users, and when a Thread was relevant to a client, we would mention them casually.

At the time, it seemed like the only way to survive on a platform known for punishing self-promotion. And for a while, it worked.

Then the FTC’s updated rule banning fake reviews and testimonials landed. Suddenly, it was obvious this approach had no future. Anything built on grey-hat methods was not going to compound. The moment enforcement or platform norms shift, the entire investment can evaporate.

So we scrapped it and committed to doing Reddit transparently.

Today, most teams we speak with understand the era of covert Reddit marketing is over. But while transparency is necessary, it's still not sufficient to make Reddit work for businesses.

Status comes before reach

Reddit’s defenses are set up to protect it from accounts with ulterior motives. If it’s obvious you’re there to shill or manipulate, they’ll figure you out pretty quickly.

In this environment, influence and reach can only be unlocked over time by building community trust first.

Every account starts with no status. Young, low-karma accounts are watched more closely and throttled more aggressively. Meanwhile, accounts that consistently contribute value earn higher status over time—their content ranks higher, and they’re trusted more and given more latitude.

To maximize reach, you have to operate within the bounds allowed to an account at your current status level while deliberately building up that status so more powerful actions become available later.

Your account status is determined by two things:

- Account Karma (how the community responds to your content)

- Thread and Comment history (how moderators evaluate you)

Every interaction contributes to a running judgment: Is this account giving more value than it’s taking? Only accounts that consistently provide value will raise their status over time.

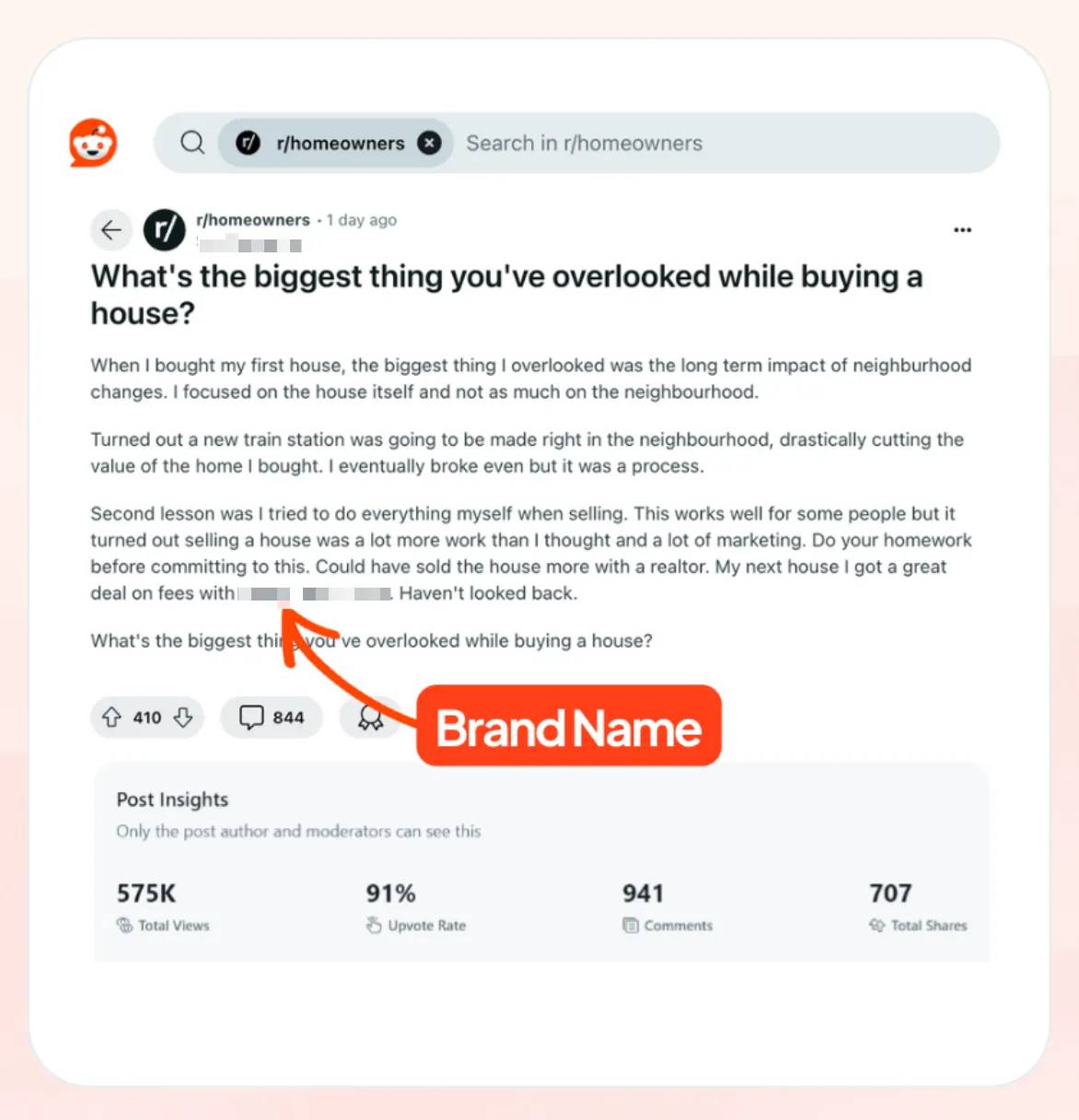

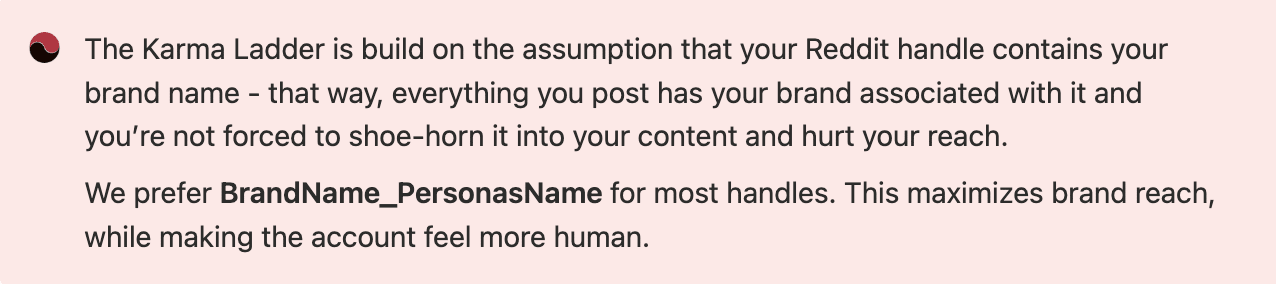

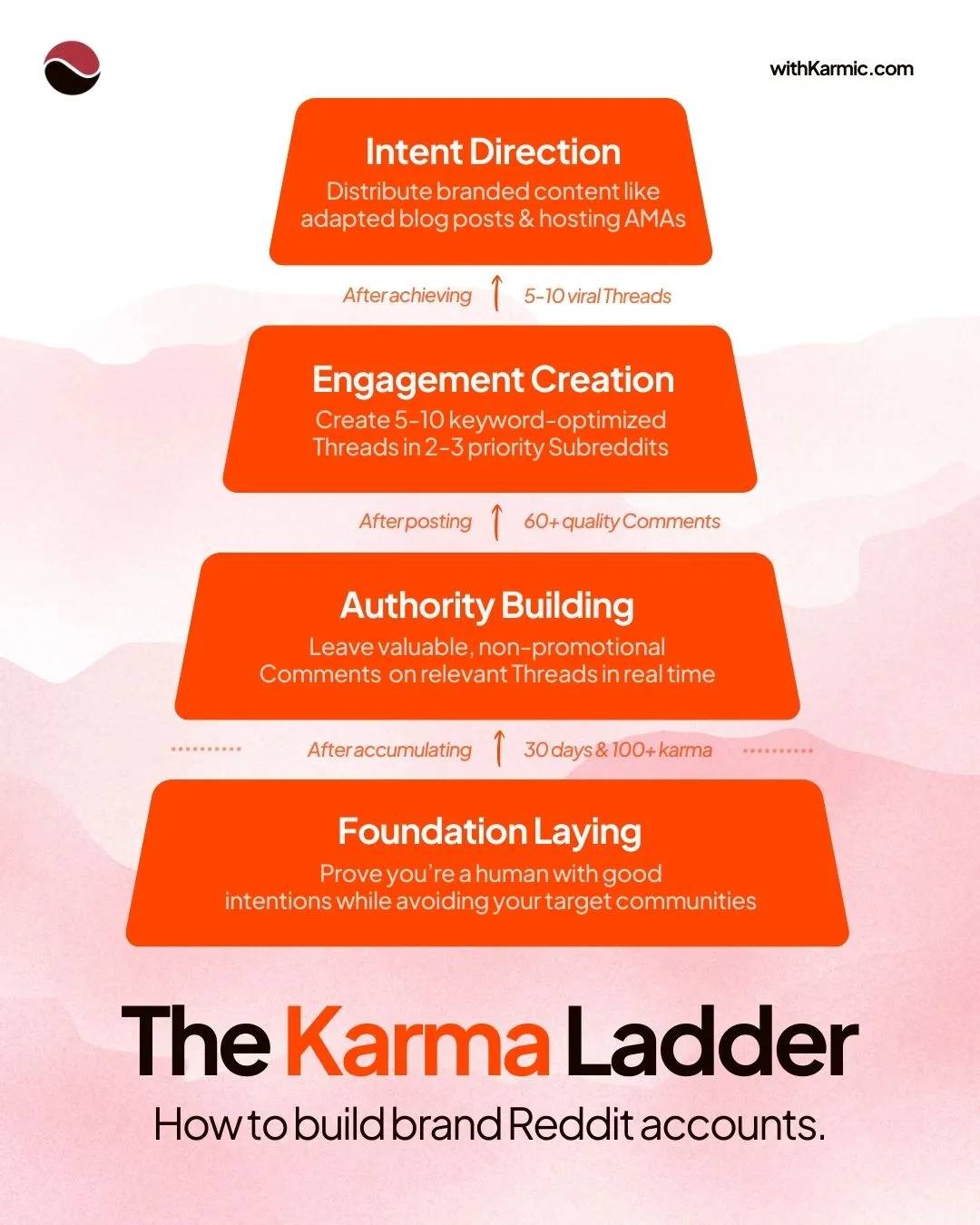

We’ve compiled our learnings on how to do this into a process we recommend for any brand building an organic Reddit presence. We call it the Karma Ladder.

Climbing the Karma Ladder

The Karma Ladder is a progression toward higher-impact Reddit activity over time, while protecting your account and content from platform risk.

Each step aims to increase reach while managing risk. The key is to operate within the bounds allowed to your account at its current status level, while deliberately building up that status so more powerful actions become available later. Each step only works if the previous step was executed properly.

Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Laying the Foundation

This phase is about looking and behaving like a real human.

Spend 30 days in subreddits completely unrelated to your business—places like r/coffee, r/books, or hobby communities. Participate in conversations and build your account Karma. The only goal is to establish baseline trust and safety with Reddit’s systems.

Most teams try to skip this step. That’s a mistake. Your account needs this foundation before it can effectively reach your target audience.

Advancement criteria:

✅ 30 days + 100 Karma

Step 2: Building Authority

Now you can start participating in Threads relevant to your target customers in real time, but only through Comments.

Don’t include links or mention yourself, but focus on adding value. Answer questions thoughtfully, share insights, and contribute to discussions without any promotional angle.

Your handle quietly associates your brand with the topic at hand while your content builds authority. This is where the real work happens (and where most competitors give up).

Advancement criteria:

✅ 60 days + 60 relevant comments

Step 3: Creating Engagement

Only once authority is established do you begin posting your own Threads. Even then, start with low-risk conversation starters designed to get the right people talking and reach as many of them as possible.

Done well, these Threads can spread widely and position your account as a curator of the most important discussions in the space. This phase also builds critical credibility with moderators, which will matter significantly when you reach Step 4.

This is often the hardest step. Getting 5-10 Threads to go viral takes skill, timing, and sometimes a bit of luck. Don’t rush it—quality matters more than speed here.

Advancement criteria:

✅ 5-10 viral Threads (100k+ impressions for consumer, 25k+ for B2B)

Step 4: Direct Intent

At this point, you’ve earned the ability to selectively direct attention. Even still, you’ll want to manage risk appropriately.

By now, you should have 500+ Karma and meaningful relationships with Subreddit moderators. Before you post anything promotional, reach out to moderators directly. Share what you’re thinking about posting and ask for their input. Most will appreciate the courtesy and give you guidance on how to do it in a way that benefits the community.

Think of this as insurance for the riskier swings you’re about to take.

Start by adapting existing thought leadership into a Reddit Thread, progress to making a company announcement, and eventually host an AMA with founders or domain experts. With moderator support, they may even sticky your AMA announcement at the top of their subreddit.

Time investment:

✅ Each step requires 2-4 hours per week of consistent engagement

Why you can’t skip steps

Everyone wants to jump straight to posting Threads. They’re visible, quantifiable, and easy to report on.

Others try shortcuts: enlisting customers to post for them, coordinating upvotes, or dropping links to track attribution. These tactics usually violate Reddit’s terms and always damage long-term reach.

Don’t take the bait.

Without a foundation of valuable Comments, your Threads are fragile. They get removed more easily, attract moderator scrutiny, and cap your future reach in ways that are hard to reverse.

Commenting is the unglamorous foundation that makes everything else work. It’s how moderators learn to trust you and how you build a defensible position. Skip it, and you’ll be treated exactly as you are: an outsider trying to extract value rather than provide it.

How to measure progress

Reddit is a dark-social channel in a link-hostile environment. That makes measurement harder, but also creates opportunity.

Track two things:

- Platform signals: Karma, impressions, and organic mentions by other users (we call these “Seeded Mentions”)

- Customer signals: Ask leads and purchasers where they heard about you, and include Reddit as an option

Some brands also track secondary signals like search visibility and LLM citations. No single metric tells the full story, so watch leading indicators while compounding effects build in the background.

Build a system, not a campaign

Successful Reddit programs are built on repeatable processes over time.

Identify the Threads your brand should join. Map the community’s recurring debates. Optimize for Reddit’s native signals, not clicks.

Most of this happens in unowned subreddits—communities you don’t control, but where trust and audiences already exist. Creating a branded subreddit can work, but takes much longer. Most teams need to prove traction first.

The Reddit organic payoff

Done right, Reddit can become one of the most powerful compounding assets in a brand’s stack.

You expand your SEO and AEO surface area by participating in (and later creating) Threads likely to rank in search and get cited by answer engines. Over time, your brand becomes familiar enough that others mention it without prompting, compounding the effect.

Engagement Threads extend your reach across the platform. Your brand name shows up next to genuinely valuable content, providing a trust halo effect. Eventually, you build an audience that knows, likes, and trusts you, who are more likely to recommend and defend you in conversations you’re not even part of.

At that point, you’ve built Reddit into a PR megaphone you can leverage when it matters.

What Reddit rewards (and what it doesn’t)

Most social platforms reward you for talking about yourself until people care. Reddit is the opposite.

On Reddit, the community supplies the context. Your job is to show up in the right places, add real value, and let that context associate you with the ideas that matter to your customers.

The brands that win on Reddit are the ones that resist the urge to promote and focus instead on earning trust through consistent contribution.

Do that well, and Reddit will give you something most platforms won’t: influence that compounds over time, reach that doesn’t require paid support, and an audience that recommends you without prompting.

It takes longer to validate than running ads. It’s harder to measure than social channels that allow links. But it’s one of the only truly compounding organic channels left.

Want to learn more? Read Karmic’s entire Ultimate Guide to Reddit Organic

Colin James Belyea

Co-Founder at Karmic Reddit Agency

Most brands get Reddit backwards

Insight from Colin James Belyea — Co-Founder at Karmic Reddit Agency

Stop Pulling the Wrong Growth Levers

Insight from Justin Setzer—Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

Last week, we examined the what vs. why trap: how growth teams conflate what happened with why it happened.

This week, we’re looking at a related problem: how teams misjudge where impact actually comes from.

We’re taught that if you have limited resources, you need to take “big swings.” The logic sounds right: you can only run so many experiments, so each one should be as impactful as possible. And the way to maximize impact? Change a lot of variables. Test a completely different page, a completely different flow, a completely different approach.

The assumption buried in there: more variables changed = bigger expected impact.

In my experience, that’s just not true. Or, more precisely: it’s not that simple.

What I Tried First

Over a decade ago, I was one of the first growth hires at Grammarly. I built their experimentation program from the ground up. At the time, a major focus was improving homepage → sign up rate.

Our funnel data pointed to that step in the funnel being a constraint (among a handful of other signals). That was the 'what' — now we needed to figure out the 'why.'

I did everything we're taught to do. I maintained a high testing tempo. I took big swings. New homepage designs, completely different copy angles, long-form pages versus short, entirely different signup flows. I was following the playbook: move fast, ruthlessly prioritize, test aggressively, ship constantly.

I was proud of our inputs.

The problem was that the conversion rate barely budged. And if I'm being honest, we weren't learning much. I was missing something.

What Actually Worked

So I did something that felt like the opposite of best practice. Instead of asking “what should we test next?” or "how do we maintain a testing cadence of X per month?", I stopped shipping. I slowed down. And I started asking why.

Grammarly had just released its browser extension and switched to a freemium model. Historically, Grammarly had been a paid product. So I started looking at our situation through the lens of how our channel, product, and model all fit together (would've been really helpful had the Foundational Five framework been a thing back then).

A few signals started pointing in the same direction:

Channel context. Most of our traffic was high-intent search traffic. People searching for “grammar checker” or similar terms. They weren’t browsing. They’d already decided they wanted something like Grammarly. But when they searched those terms, the results were full of clearly free alternatives. Low quality, but free. Our visitors were being primed to expect free before they even landed on our page.

User feedback. I talked to our support and social teams. One of the most common questions they were fielding: “Is Grammarly free?” We had a perception problem leftover from the paid-only days.

User behavior. Heatmap data and user recordings showed that most users spent little time exploring the page. Per the channel context, they knew what they wanted.

Put it all together, and the hypothesis became clear: these visitors need to know it’s free, and they need to see it exactly where they’re making the decision.

So I added “it’s free” to the CTA buttons. Less than a minute to build.

The result? About 8x the lift of any other experiment I’d run. And probably a top ten result out of hundreds of tests during my time at Grammarly. At least from a sheer conversion rate standpoint.

Two words. Not a new page. Not a new flow. Not a big swing. Two words that solved a real problem because I’d finally stopped to figure out where the actual leverage was.

The Point Isn't Micro vs. Macro

It’s tempting to take this and conclude: small tests beat big tests. That’s not what I’m saying.

What I’m saying is that in my experience, the relationship between the size of an experiment and its impact can be unintuitive. The thing that determines impact is whether you’re hitting the right lever. And just like with product, "the right lever" means solving a fundamental problem for your user.

Here’s a silly way to think about it that I share with teams I advise. What’s the single most impactful change any company could make to their funnel?

Remove the buy button.

If you have a 5% purchase rate and you take away the button, you now have a 0% conversion rate. One variable. Maximum impact. Obviously absurd, but it proves the point. Impact doesn’t come from how much you change. It comes from solving user problems (or in this case, creating them 😅).

Finding Your Levers

So how do you find your version of “it’s free”?

The short answer: you have to slow down and do the work that most teams skip.

At Grammarly, I didn’t stumble into the answer. I looked at the data to understand where the problem was. I talked to customer-facing teams to understand what users were actually confused about. I studied the competitive landscape to understand what expectations visitors were coming in with. I observed actual users as they navigated the site. Each signal on its own was just a clue. Layered together, they pointed to an answer I never would have found by just shipping more tests.*

That’s the pattern. Quantitative data tells you where to look. Qualitative research helps you understand why. And frameworks like the Foundational Five help you see how the pieces connect so you’re not just looking at isolated metrics.

Most teams skip the qualitative layer entirely. Shipping new tests is exciting. Digging into user psychology, talking to support, studying the competitive landscape? Not so much. But that slow work is where the real leverage gets uncovered.

*I certainly could've produced the same result through brute force. But I wouldn't have gotten the same learning. It's entirely possible we would've eventually built a random variation that happened to include "free" in the CTA. It may have increased CR%, but we wouldn't have had any clue as to why. Again, that 'what vs. why trap' from last week.

What’s Next

I realize we’ve now spent two editions talking about common experimentation mistakes without fully answering the question: how do you actually do this well?

That’s coming. I'm working on a more tactical breakdown and hope to share that next week. Stay tuned!

Justin Setzer

Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

Stop Pulling the Wrong Growth Levers

Insight from Justin Setzer—Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

The What vs. Why Trap

Insight from Justin Setzer—Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

I recently started advising an up-and-coming startup. In one of our first sessions, I sat in on their weekly growth meeting.

They kicked it off by reviewing the experiments pipeline. At the 5-minute mark, they switched gears and took a look at key metrics.

Now, 10 minutes into the meeting, the head of growth headed off a couple of potential rabbit holes and announced it was time to talk learnings.

So far so good 👏. They’re already demonstrating more process and discipline than most.

Their paid marketing lead kicked things off. She just wrapped up a batch of ad creative tests on Meta and was clearly eager to share what was learned. It went something like this:

“Our competitors predominantly run ads featuring male models. And the market is getting tired of it. People are starting to feel like the other brands don’t ‘get them.’ So, we hypothesized that ad creatives featuring female models would allow us to not only stand out, but also build trust with our market.”

Love that they’re taking a hypothesis-driven approach. But I think I see where this is headed…

She then walked us through the data. By every traditional success metric, the new creatives outperformed the control.

“Great result. But what can we learn from this test?” asked the head of growth.

“We’ve learned that creative featuring female models performs best with our audience. Our hypothesis was right. Our market is tired of the incumbent brands. This is how we differentiate. This feels like a huge learning that should be applied across all of our marketing surfaces.”

The head of growth nodded in agreement. A brief discussion took place about next steps for applying those learnings more broadly. And then they moved on.

Uh-oh. 😬 Think we might’ve found our problem.

So what went wrong here? They conflated “what happened” for “why it happened” – or what I call the ‘what vs why trap.’

Here’s what they learned: A couple new ad creatives featuring female models produced a higher ROAS than their champion variations that don’t. That’s it.

You know what they didn’t learn? Why.

Was it because the model was a woman? Maybe. Or maybe it was Meta’s algorithm. Could there have been some kind of cultural dynamic at play? Certainly possible. Right alongside a million other possibilities.

The bottom line is that an ads test, like any other quantitative testing method, can only tell us what happened. It provides clues as to the why (which is super valuable). But that’s as far as it goes.

Why This Matters

When I introduce this concept to teams for the first time, it’s not uncommon to get pushback.

“OK, I get that you’re technically right. Maybe we can’t prove the why with 100% confidence, but this is close enough, right?”

Nope.

“Fine. So we just need to do a better job with our experiment design. If we can isolate a single variable and prove it’s responsible for the observed effect, then we’ll have our why, right?”

Nope again.

“Wtf are you talking about, bro? We only changed 1 variable. It’s the only possible explanation for the result.”

Maybe. But it still doesn’t tell us why.

At first, this can feel a bit pedantic. It’s not.

For a later-stage company, years of rich, compounding learnings can serve as a moat. All things equal, a team that knows more about its customers and market than anyone else will win.

For early-stage companies, it’s an existential matter. At the end of the day, a startup is just a collection of unproven hypotheses. Product-market fit being the most fundamental. “We believe this audience has this problem and will pay for this solution."

Learnings are how you validate or invalidate those beliefs. If your learning system is broken, you can't course-correct. You drift further from reality with every decision.

Getting Closer To The "Why"

At the highest level, experimentation methods can be put into one of two categories:

- Quantitative methods

- Qualitative methods

So far, we’ve been talking about numero uno. Think A/B tests, funnel data, cohort analyses, heat maps, etc. They all have one thing in common. They do a great job of telling us what happened or where a constraint may exist, but they can’t tell us why.

Have a new LP that’s converting at a higher rate than your control? That’s a what.

Funnel data showing a major dropoff? A what.

Cohort analysis showing significantly lower retention for a particular customer segment? Another what.

And these “whats” are extremely important. They give us clues. Clues that can be used to form new hypotheses or shape existing ones. And that’s where the team I’m advising went wrong. They mistook their Meta Ads experiment as validation of their entire hypothesis. And they were ready to shift their whole GTM strategy accordingly.

But here’s something that the ultra data-driven teams don’t like to hear: it’s impossible to answer “why” through quantitative methods alone.

Which brings us to the second category: qualitative methods. User interviews, surveys, and so on.

Most growth teams skip the qualitative layer. Shipping new tests is fun. Mining through big data sets—yummy.

Slowing down to talk to customers? Not so much.

But if the goal is to maximize the quality of our learnings—and hopefully I’ve made a compelling case for why that should be the goal of any growth team—then you need both.

Quantitative to tell you what's happening. Qualitative provides the human context to get closer to why.

Closing Note

The keyword is "closer." We'll never know with 100% certainty why humans behave the way they do. But we can triangulate. Layer different types of evidence. Get close enough to make better decisions.

Most teams treat learnings like a checkbox. Test ran. Winner picked. Learning logged. Move on.

But a learning that's wrong is worse than no learning at all. It compounds in the wrong direction.

So before you log your next "learning," ask yourself: have we done the work to get closer to why? Or are we only at the "what happened" layer?

If it's the latter, you're not done yet.

Justin Setzer

Demand Curve Co-Founder & CEO

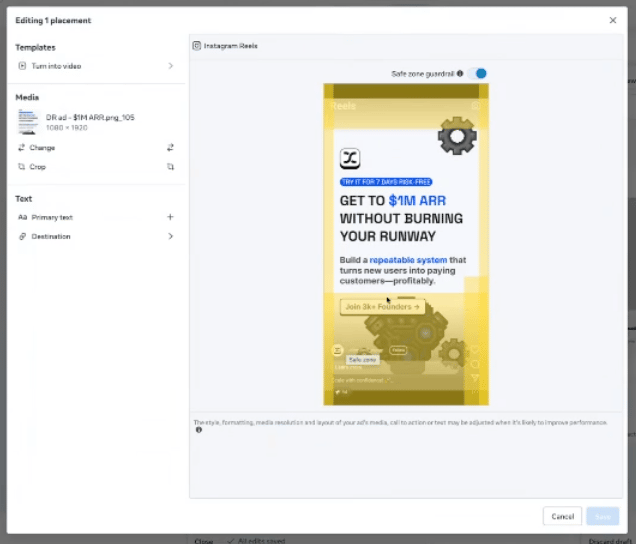

Your ads need a safe space, too.

Insight from the DC Team

Why this keeps happening

Meta doesn’t show your ad once. It shows it across multiple placements, each with different dimensions, UI overlays, and visual constraints.

When advertisers design for a single format and assume Meta will handle the rest, the platform does exactly that. It handles it. Not carefully or contextually. Just mechanically.

I'm sure that Meta will eventually be able to auto resize any creative to fit the ad placement, but as of today, it isn't reliable enough to just let it do it's thing.

Auto-cropping doesn’t know where your value proposition lives.

It doesn’t know which line of text matters most.

It doesn’t care if a CTA ends up half-hidden.

The tricky part is if your creative gets cropped strangely, nothing necessarily breaks. There are no red flags and the ad still runs fine. You may not even know about it until you get that late night Slack. But performance (and your brand image) degrades in ways that are hard to diagnose after the fact.

What “safe space” actually means

Every placement has zones where important content should not live.

Instagram Feed crops square images differently than Facebook Feed.

Reels push content upward because of interface elements at the bottom.

Stories reserve space for controls and CTAs.

Meta will happily run the same asset everywhere. That does not mean it will look good everywhere.

Meta adds interface elements on top of your creative.

Buttons.

Usernames.

CTAs.

Modals that slide up from the bottom.

If your core message lives too low on the canvas, it gets covered.

There's an easy step to make sure your ads always look sharp. When you edit placements in Ads Manager, Meta shows you a yellow “safe zone.” That’s the area you actually control.

Anything outside it is at risk.

The most common mistake we see

Easily the most common mistake advertisers make is using a single 1:1 asset for all feed placements.

Square creatives technically work in Instagram Feed, but they are far more likely to be cropped in ways that feel sloppy or unintended. Headlines get squeezed. Visual balance gets lost. Brand cues drift.

Reels introduce a different problem. The interface pushes content upward, which means anything designed without that in mind can end up competing with Meta’s own UI.

Stories look similar to Reels, but the safe space is different. Treating them as interchangeable usually leads to subtle but real issues.

None of this requires advanced strategy to fix, just an extra step or two.

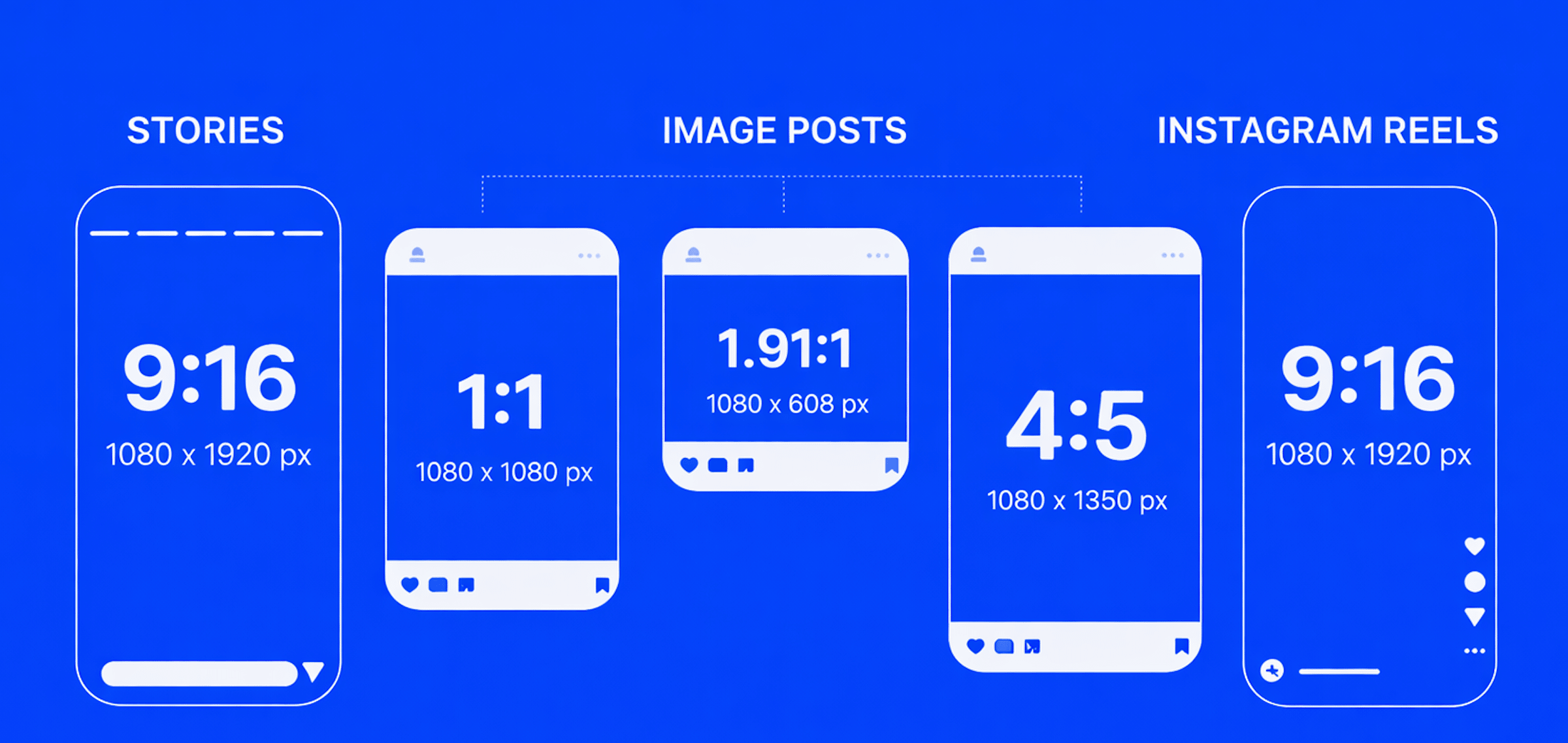

Table stakes for a smooth campaign

Before launching anything for our clients at Demand Curve, we check three things.

First, we never rely on a single asset.

At minimum, we have:

• A square (1:1) version

• A 4:5 portrait version for feed

• A 9:16 version for Stories

• A slightly adjusted 9:16 version for Reels

Second, we design with safe space in mind.

Not centered “roughly,” but actually inside the guardrails.

Third, we preview every major placement manually. Anything labeled “feed” gets a 4:5 version. Reels and Stories each get their own version, even if the differences are minor. Every ad is previewed across placements before it goes live.

This is not about obsessing over design (which is another post altogether.) It’s about removing avoidable friction between the ad and the person seeing it.

Why this matters more than it seems

Safe space issues rarely tank performance outright. What they do instead is erode trust.

Ads that feel careless or awkward create hesitation. Hesitation lowers engagement. Lower engagement pushes delivery in the wrong direction.

Fixing this doesn’t create upside on its own. It removes unnecessary downside. That’s usually the better trade. :)

If you want help running Meta ads that actually impact your bottom line, we run paid acquisition for a small number of high-growth companies. If you're spending $50K+/month on Meta and you want someone who obsesses over these details, we should talk.

— The Demand Curve Team

Your ads need a safe space, too.

Insight from the DC Team

Why your customers might be bailing at checkout

Insight from Joey Noble — Demand Curve Creative Strategist

Let me paint two different checkout experiences.

Your internal view: A logical sequence of necessary steps. Collect shipping address (we need to know where to send it). Verify payment method (we need to get paid). Confirm order details (reduce support tickets). Each step has a reason.

Your customer's experience: A gauntlet of “should I keep going?” decisions. Every new page is another chance to reconsider. Every form field is mental effort their brain wants to avoid. Every unexpected element triggers doubt. You think you’ve built a logical flow, but they’re just feeling the drag of another screen, another field, another decision.

This is why your checkout “makes sense” to your team but has a 60% abandonment rate. You’re designing for logical progression when you should be designing for psychological momentum.

When someone clicks “checkout,” their brain runs three assessments that determine whether they complete the purchase:

- Should I even start this?

- Should I keep going?

- How do I feel about this?

Most founders optimize none of these. They just replicate what they’ve seen on other sites, not understanding why those patterns work (or don’t).

Let’s break down what’s really happening at each stage, and the specific tactics that increase completion.

They're deciding whether to start in a few split seconds

Someone clicks “checkout” from your cart page. Before they enter a single piece of information, their brain is scanning for reasons to abandon.

This happens almost entirely subconsciously. They’re not thinking, “let me carefully evaluate whether this checkout is trustworthy.” They’re getting a gut feeling about whether this is going to be annoying.

Two questions firing rapidly: “Does this look safe?” and “Is this going to be a pain?”

If either answer is wrong, they bounce before starting.

Make trust instantly obvious

Your checkout needs to look boringly conventional in all the right places. Standard layout. Familiar payment logos. Orthodox security badges.

This isn’t the place to get creative with design. Every unconventional choice forces their brain to evaluate “is this legitimate?” instead of just proceeding.

Put SSL indicators and security badges above the fold. Not because customers consciously check them, but because their absence triggers suspicion.

Show accepted payment methods immediately—Visa, Mastercard, PayPal, Apple Pay. If they see their preferred method isn’t available, they’re gone.

Display testimonials or trust signals on the checkout page itself. “2,847 orders completed this week” or a specific customer quote about delivery speed removes the “am I the first person taking this risk?” concern.

Show them the whole journey upfront

Nobody wants to start a journey without knowing how long it’ll take.

Display progress indicators at the top: “Shipping → Payment → Confirmation” or “Step 1 of 3.” This reduces anxiety about unknown length and creates commitment through progress tracking.

Make it look shorter than it feels. Three clear steps feels easier than seven micro-steps, even if the total fields are identical.

Summarize what’s in their cart with images and prices. They need to quickly confirm “yes, this is what I wanted” without recalculating whether it’s worth it.

What kills momentum immediately:

Surprise costs. If shipping wasn’t shown on the product page and suddenly appears at checkout, you’ve violated their mental budget. They’ll abandon to “think about it” (translation: find it cheaper elsewhere). Always show shipping costs before checkout, or make it free.

Forced account creation. “Create an account to continue” is a brick wall for anyone who just wants to buy once and leave. Offer guest checkout prominently. You can ask them to create an account after they’ve paid—when they’re relaxed and their card isn’t on the line.

The first screen of checkout isn’t about collecting information efficiently. It’s about passing a gut-check that determines whether they’ll start at all. You can have the most optimized multi-step flow in the world, but if the first screen triggers doubt, nobody sees step two.

Make continuing easier than reconsidering

They’ve started to enter their information. Every new field, every new screen, every unexpected element is a fresh opportunity for their brain to ask: “Should I stop?”

Water flows downhill. Mental effort flows toward the easiest path. Your job: make completing checkout easier than abandoning.

Most checkout abandonment doesn’t happen because people don’t want the product. It happens because continuing requires more mental energy than their brain wants to spend.

Reduce decision points aggressively

Every choice is friction. Every dropdown is a chance to second-guess.

If you’re asking for “company size” or “industry” during checkout, you’re creating unnecessary decision points. Default to the most common option and move forward. Collect better data later through email or in-app.

Don’t ask “Residential or business address?” unless it actually changes something. Just ask for the address.

Consider whether you need phone numbers for every order. If it’s not critical for delivery, don’t ask.

Each removed field is compound improvement—less typing, less decisions, less mental effort.

Make forms feel effortless

Use address autocomplete. As they type “123 Bak…” suggest “123 Baker Street, London” with city and postal code filled automatically.

Pre-populate country based on their IP address. If 90% of your customers are in the US, default to that.

Show sample formats in form fields: “email@example.com” in the email field, “123 Baker Street” in the address field. This stops them from thinking, “wait, what format do they want?”

Enable social sign-in if you absolutely must collect account information. “Continue with Google” is one click versus typing name, email, creating password, and confirming password.

Handle errors without killing momentum

When they enter information incorrectly, don’t wait until they click “continue” to tell them. Show inline validation: “Email address needs an @ symbol” appears immediately, while they’re still in the mental context of that field.

Make error messages helpful, not punishing. Not “Invalid format” but “Phone number should be 10 digits.”

Never clear the form when someone makes a mistake. Nothing kills momentum faster than having to re-enter six fields because one was wrong.

Offer the path of least friction for payment

Provide multiple payment options. Credit card, PayPal, Apple Pay, Google Pay. Each missing option is a percentage of customers who’ll leave to “think about it.”

Consider “Buy Now, Pay Later” options like Affirm or Klarna, especially for purchases over $100. Breaking $400 into four $100 payments changes the mental math from “can I afford this?” to “can I afford this monthly?”

Don’t force them to leave your site to complete payment. Embedded payment forms (using Stripe or similar) keep them in your environment. Every redirect is an opportunity to reconsider.

Be careful with discount code boxes

Prominent promo code fields can hurt conversion. When someone sees “Enter promo code,” their brain immediately thinks “wait, am I paying more than I should?” If they don’t have a code, they’ll often abandon to go search for one and possibly get distracted by competitors.

If you must include it, make it subtle. Small “Have a code?” link that expands, rather than an empty field demanding attention.

You’re not trying to extract maximum information per transaction; you’re trying to minimize reasons to quit. Every field you remove, every decision you eliminate, every piece of friction you reduce increases the odds they reach the end.

The ending determines whether they complete and return

The last 30 seconds of checkout determine not just whether they complete this purchase, but how they feel about your brand going forward.

People don’t remember experiences as averages. They remember peaks and endings.

Mediocre checkout + strong ending = remembered positively.

Smooth checkout + weak ending = remembered negatively.

Your confirmation page isn’t an afterthought. It’s either depositing positive psychology or withdrawing it.

Before they click “Complete Order”

Show a complete order summary before final confirmation. Product, shipping address, total cost, everything in one place. This removes the “wait, did I enter everything correctly?” anxiety.

Make the final CTA unmistakably clear: “Place Order” or “Complete Purchase”—not “Submit” or “Continue.” They need absolute clarity about what happens when they click.

Never surprise them on the confirmation page. If the total shown at review is $147, the confirmation page better say $147. Any discrepancy triggers “did I just get charged more?”

The confirmation experience matters more than you think

Don’t just say “Order confirmed!” and dump them to a blank page.

Tell them exactly what happens next: “Your order is confirmed. You’ll receive a shipping notification within 24 hours. Your package will arrive by Thursday.”

Include order number prominently. This is their psychological proof the transaction completed.

Provide immediate access to order tracking. “Track your order” link right on the confirmation page. They don’t have to dig through email.

Avoid the immediate upsell trap

Your growth instinct says “they just bought, ask them to refer friends!”

You should resist this.

They just completed a mentally taxing process. Their brain needs resolution, not another ask. Let them breathe for a minute.

Save the “refer a friend” ask for the follow-up email, after they’ve received the product and are happy. The confirmation page should feel like relief, not the start of another conversion funnel.

The first follow-up matters

Send order confirmation email immediately.

Include everything: what they bought, when it ships, how to track it, how to contact support.

Make it feel personal. Not “Order #47382 has been confirmed” but “Your [product name] is on the way.”

Consider a day two or day three check-in: “Your order should arrive tomorrow. Reply to this email if you have any questions.” This demonstrates you’re thinking about their experience, not just the transaction.

Build the return path early

Most retention efforts start after the first purchase. I think this isn’t the right way to think about it. Instead, retention starts in the first interaction, or the first impression.

Every checkout experience deposits or withdraws psychological goodwill. If the process is smooth, trustworthy, and clear, they’ll buy again and forgive minor issues. Frustrating, confusing, sketchy-feeling = they’ll churn at first friction.

Make your confirmation page and follow-up emails feel like the start of a relationship, not the end of a transaction.

“Welcome to [brand]” instead of “Order confirmed.”

“Here’s what to expect” instead of “Track your package.”

Small language shifts that reframe purchase as a beginning, not a conclusion.

Where to start

Pull up your checkout analytics. Find the biggest drop-off point. That's your starting point.

Run this three-part audit:

- Put your checkout URL in an incognito window. Before entering any information, does it instantly feel safe and straightforward? Would you trust it with your credit card if you'd never heard of the company?

- Count every form field, every dropdown, every choice. Can any be removed or defaulted? Time yourself completing the flow. Every extra 10 seconds is meaningful abandonment.

- Read your confirmation page and email out loud. Does it feel like resolution or abandonment? Does it clarify what happens next or leave them wondering?

Fix the biggest friction point first. Test. Then move to the next.

These improvements compound.

Better initial trust → more start.

Less friction → more continue.

Better endings → more complete and return.

Small changes have outsized impact because you're working with human psychology, not just interface design. Remove one unnecessary field and you might see 5-10% lift in completion. Remove three and you could see 20%+.

The founders who win aren't the ones with the most features or the slickest design. They're the ones who make buying feel effortless.

Your customers aren't carefully evaluating your checkout. They're making rapid gut calls about whether to continue. Design for their reality, not your ideal, and watch completion rates climb.

Joey Noble

Demand Curve Creative Strategist

Why your customers might be bailing at checkout

Insight from Joey Noble — Demand Curve Creative Strategist

The four flywheel types

Insight from Devon Reynolds — Demand Curve Creative Strategist

First, a quick reset: what we mean by a flywheel

A flywheel isn’t just “a thing that helps growth.”

A real flywheel has three properties:

- Each new user makes the product more valuable for the next user

- The system reinforces itself without proportional effort

- The advantage gets harder to copy as it scales

If growth requires the same input every cycle, you don’t have a flywheel. You have momentum. (Momentum is great of course, but flywheels are better.) ;)

Flywheel #1: Network effects (the gold standard)

What it is

This is the cleanest flywheel to understand, and the hardest to fake.

A real network effect means that when someone new joins, existing users get more value without you having to do anything extra.

Think about a marketplace. More buyers attract more sellers. More sellers improve selection. Better selection attracts more buyers. Each loop makes the product more useful than it was before.

Common examples

- Social networks

- Marketplaces

- Collaboration tools with cross-user interaction

How it actually works

- More users → more value for everyone